One of the essential rites of passage for a native Texan is that first, confusing visit to a Dairy Queen outside of the state. Sure, a Dairy Queen in Maryland or Missouri will happily sell you a Blizzard and a Dilly Bar. But where’s the steak-finger country basket, the chicken-fried-steak sandwich called the Dude, or any burger belonging to the Buster family, be it Hungr-, Belt-, or Triple-? And why aren’t the posters on the walls emblazoned with the phrase “That’s what I like about Texas,” a line lifted from a catchy jingle that’s more familiar to young Texans than our official state song? (It’s “Texas, Our Texas,” kids.)

These details are so central to the Texas DQ experience that it would be jarring to cross over our border into Arkansas, stop at the DQ on Magnolia’s Main Street, and see only chicken fingers—no steak!—accompanied by the numbingly banal tagline “Happy Tastes Good.”

And yet, fifty years ago, few of those favorite foods existed. The Hungr-Buster didn’t show up until 1974, and the country basket wasn’t trademarked until two years later. And that iconic jingle? It didn’t hit airwaves until 2002, as part of a very successful ad campaign.

But one institution that was around in 1973 was the Texas Dairy Queen Operators Council (TDQOC). This co-op of Texas franchise owners was essential to putting the Texas in Texas Dairy Queens. It’s thanks to the TDQOC that the chain became such an integral part of our culture that Larry McMurtry used it in the title of one of his memoirs.

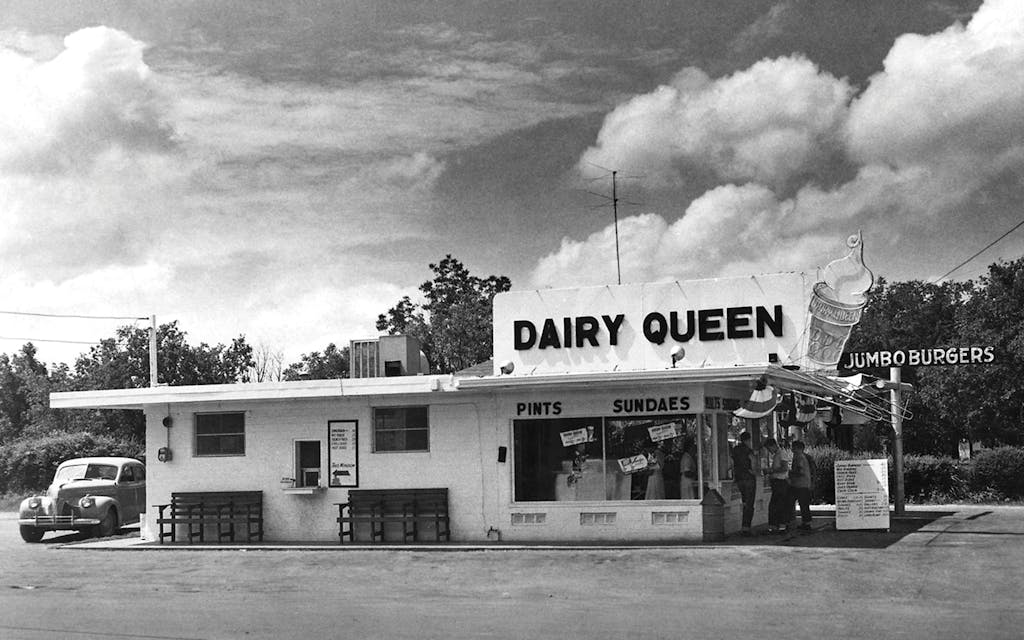

The origins of the TDQOC date back to 1947, when Rolly Klose opened Texas’s first DQ franchise, in Austin. Dairy Queen’s Illinois-based founders had also sold Klose the rights to the entire Texas territory, which allowed him to sell franchises to nearly anyone. Klose ran his business informally; he lent money to aspiring restaurateurs and scribbled contracts on napkins. “Bob bought ours directly from Rolly, who was in his pajamas, out in the garage,” recalls Jennifer Bowen, a DQ operator whose late husband purchased his first franchise, in Falfurrias, in the early seventies. Klose, who occasionally sealed deals in his daytime clothes as well, kept busy, and by 1973 there were more Dairy Queens in Texas than in any other state.

Because Klose was pretty hands-off, his franchisees felt free to update their menus however they wanted. While national Dairy Queens focused largely on desserts, Texas owners started selling burgers and other savory foods as early as the fifties. After all, they had to compete with Whataburger. That fast-growing, Corpus Christi–based chain was tightly controlled by the Dobson family, which gave its franchisees advantages of scale and reassured customers that when they walked into a Whataburger, they’d know what they were going to find. To bring that kind of consistency to Texas’s hundreds of DQs, franchise owners established the TDQOC to standardize menus and pooled advertising money that funded Texas-specific campaigns—much as Chevrolet and Ford make truck commercials specifically for the Texas market.

Perhaps the TDQOC’s greatest accomplishment is that it still exists. Rolly Klose sold his Texas territory rights back to DQ in 1980, and the bigwigs (who by then were based in Minneapolis) tried to tell the Texans what to put on their menus and how to spend their advertising dollars. The Texans, being Texans, didn’t take kindly to that and filed suit, charging fraud and misrepresentation, in 1991. “We reached a settlement agreement in 1992, and we just peacefully coexist,” says Bill Hall, a former TDQOC president. “They have continued to change our royalty contracts, but they have to accept our use of Texas Dairy Queen products and let Texas do its own advertising—unless they can get the majority of Texas operators to agree to go to their system. And that will be hard to get, because these people love their independence too much.”

Despite that victory for Texas exceptionalism, Dairy Queen no longer has the footprint here that it once did. In 1980 DQ boasted 1,008 Texas locations; today there are fewer than 600, a collapse that can be blamed partly on a Dallas investment firm that bought dozens of Texas DQs and then declared bankruptcy. Many small towns where a Dairy Queen was once the main gathering place are now without one, a major blow to our rural communities.

The Texas menu has changed over the years, though only for the better. It now features fried jalapeños, steak fingers infused with pepper jack cheese, and, sometimes, guacamole. But you can still get a Hungr-Buster, a country basket, and the Dude, and you can still hear that classic jingle. (In 2022 it got an update by Lubbock-born country star Josh Abbott.) Much remains the same. No matter which Midwestern conglomerate owns the company—as of right now, it’s Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway—Dairy Queen is still what we like about Texas.

This article originally appeared in the February 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “DQ, Our DQ.” Subscribe today.