Stephen, a Houston restaurant manager who is profiled in Ricardo Nuila’s new book, The People’s Hospital: Hope and Peril in American Medicine (Scribner), has health insurance when he learns that cancer has invaded his tonsils. But, like so many Americans, he discovers only after getting sick that his bargain-basement policy won’t pay for the care he needs. The ER at a local hospital charges him $639 for his diagnosis, and then a social worker advises him to do the unthinkable: go to Ben Taub, the city’s public hospital. “This is gonna be hell,” he thinks. “I have hit bottom.”

Stephen is in for a surprise. Even after he loses his insurance altogether, he receives affordable, state-of-the-art care at Ben Taub. Scaffolded by stories like Stephen’s, The People’s Hospital makes an argument that will surprise many readers: in this tax-funded facility, we find a model not only of superb care for the poor but of how better care could be delivered to all of us.

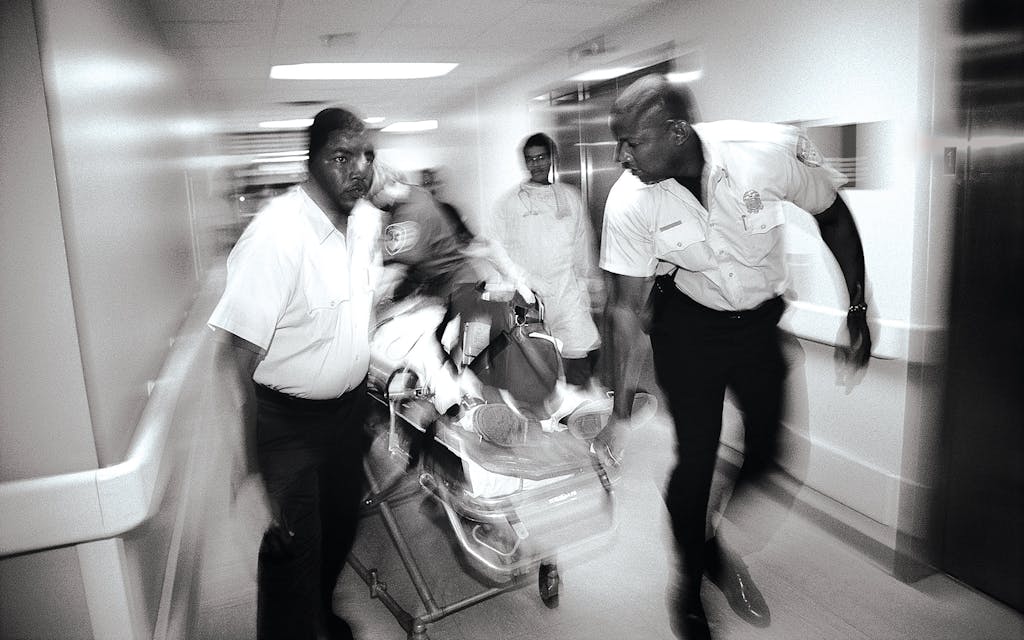

Nuila, a doctor at Ben Taub who has written for Texas Monthly, traces the dismal reputation of big-city safety net hospitals to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when dingy, underfunded, and understaffed public institutions were rightly feared by rich and poor alike. A report coming out of Houston’s sole public hospital in the early sixties described “staph infections roiling the maternity ward, killing dozens,” newborns “crying for milk that wasn’t there,” and “patients sitting in their own filth waiting days to see a doctor.” Nuila shows how, beginning in that decade, public investment in programs such as Medicare and Medicaid vastly improved the situation.

Most crucially for Ben Taub—named after a local philanthropist from an immigrant family who made his fortune in real estate—Houston voters in 1965 approved the creation of a taxpayer-funded hospital district that’s now called Harris Health System. Today, Harris County residents earning as much as 150 percent of the federal poverty level qualify for a Gold Card, which ensures access to near-comprehensive primary, specialty, and hospital care on a sliding scale payment plan.

This sort of system is hardly typical in the rest of Texas. Although the Legislature mandated in 1985 that counties fund medical care for the indigent, the state allows them to define who qualifies and gives them wide latitude to choose which services will be covered. I trained to be a physician in Galveston, where many poor and working-class patients didn’t qualify for indigent care (a situation made worse by the state’s refusal to expand access to Medicaid). I saw patients suffer and die from diseases that I knew were treatable. Occasionally, one of our unfunded cancer patients would secure an address in Houston and, finally, qualify for lifesaving treatment with a Gold Card.

The People’s Hospital details, in luminous prose, how patients from a relatively broad economic spectrum find care at Ben Taub. One of Nuila’s patients, a Salvadoran immigrant named Roxana, was uninsured when she was diagnosed with cancer in a major blood vessel. She underwent surgery through the charity program of a local nonprofit hospital, but when a surgical complication left her with gangrene in all four limbs, the hospital declined to provide further treatment. She was sent home, unable to walk or use her hands, with dead flesh hanging from her body.

Eventually, a hospice nurse referred her to Ben Taub, where she got a Gold Card. This allowed her to undergo partial amputations of all four limbs—a brutal but necessary series of procedures that, after she received prostheses, access to a wheelchair, and intensive therapy, helped her become reasonably independent once again.

Nuila writes about other patients who find themselves lost in a maze of ill-coordinated and unhelpful private care until they land at Ben Taub. Virtually all express satisfaction with the treatment they receive.

I believe these stories of satisfaction and gratitude. I work as a pediatrician at a San Antonio safety net facility, and families thank me every day. (Full disclosure: Nuila and I sometimes cross paths professionally.) This is not just an effect of the disenfranchised being grateful for any scrap of medical assistance they can get. Even wealthier families, who are sent here by helicopter or ambulance when a child is seriously injured—we’re the only Level 1 pediatric trauma center in and around Bexar County—often express pleasant surprise to me about the good care they’ve received at a public hospital.

How does Ben Taub do it? Nuila shows that care within Harris Health is affordable; each patient in the system costs the county considerably less than what the average patient costs Medicare and private insurance companies across the country in a year. Harris Health’s coverage is near comprehensive, offering virtually everything except organ transplants, which are prohibitively expensive. In some categories, such as timely response to heart attacks, care at Ben Taub is demonstrably excellent. And the system allows for innovation. For example, the hospital has become a leader in evidence-based responses to obstetric hemorrhage, a move necessitated by Texas’s above average mortality rates for pregnant and recently pregnant women, particularly Black women.

Nuila does explore the limits of locally funded medical care. One of the patients he profiles, a 36-year-old named Geronimo, lingers in Ben Taub without access to the liver transplant that could save his life. Nuila identifies privacy—individual rooms, for example, and less crowded ER waiting areas—as an aspect of for-profit care that most Ben Taub patients don’t have access to. The Gold Card model offers less choice in general: Well-insured patients and those on Medicare can choose which hospitals to go to and, often, which doctors to see. Gold Card patients, by contrast, have access only to Harris Health clinics and Ben Taub. They also face bottlenecks when seeking expensive diagnostic procedures, such as MRI scans, and long waits for elective surgeries.

But Nuila argues that a system with “brakes” actually provides better care. This is because, as multiple studies have shown, much of what the typical physician does is unnecessary and potentially harmful. For example, Nuila writes, some patients who are waiting for an MRI learn that they didn’t need it after all. The standard health care model perversely incentivizes doctors to do more, driving up costs without benefiting patients. Why, for example, do so few American patients with kidney disease choose at-home dialysis, which is often more convenient and cheaper than in-center dialysis? Part of the reason appears to be that the physicians who guide patients’ choices make more money when a patient chooses the pricier option.

As excellent as Ben Taub may be, many Texans are—or should be—uncomfortable with a racially and economically segregated health-care system in which the well-off enjoy a wide range of options and the less well-off have only one. Even if the only hospital available to the less affluent offers high-quality care, “separate but equal” should be regarded as unacceptable in the United States.

Though Nuila’s cogent storytelling and marshaling of data makes a strong case that Ben Taub is an excellent facility, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recently gave Harris Health, including Ben Taub, a rating of two out of five stars for overall quality—up from one out of five in 2019. Nuila points out that the CMS metric has widely been criticized for being unfair to public hospitals, which care for the poorest and sickest patients. It doesn’t take into account our patients’ vulnerability or the ongoing social barriers to care that they face after leaving the hospital, both of which skew our success rates.

We ought to remain wary of a health system that is profoundly segregated by race and class, even if it feels good to work in its public arm.

It’s very difficult to meaningfully compare quality across health systems. At the same time, it’s easy for a gifted storyteller—particularly a physician in a public hospital who gets thanked a lot and works on the righteous side of an often-dehumanizing health system—to make too sunny an assessment. We ought to remain wary of a system that is profoundly segregated by race and class, even if it feels good to work in its public arm.

Though he never quite says so, Nuila seems to agree. The People’s Hospital argues for something akin to the sort of taxpayer-funded health-care system found in virtually every other developed country—and the ones available in the U.S. to patients who qualify for Medicare and Medicaid. The book posits Ben Taub as a model of how a nationwide single-payer system might work. This argument is particularly potent in Texas, a state where nearly one in five residents is uninsured—the highest rate in the country. (Americans who lack health-care coverage are 6 percent more likely to die prematurely in any given year.)

Our cities are not the only places where patients are falling through the cracks. Rural clinics and hospitals are shuttering at an alarming rate, and Texans who rely on those institutions are struggling to access any kind of medical care. If a national health system could be as effective, affordable, and accessible as Texas’s most robust county systems, I would gladly be a patient in it as well as a physician.

In fact, I am a patient in the public system—I had my first child at the safety net hospital where I work and expect to give birth there again this spring. There was no fancy birthing tub or on-site Starbucks, but as a higher-

risk mother I felt safe knowing that an excellent neonatal ICU was available just upstairs and that the delivery teams were experienced enough with high-risk births to be unfazed by mine.

In the end, we didn’t need the NICU. Our treatment was first-rate and reasonably priced, and I came away amazed to have been so thoroughly cared for. If that’s the sort of medicine Ricardo Nuila and his colleagues are offering at Ben Taub, he has every right to be proud of it. And Texans have every right to demand that we all get access to it.

Rachel Pearson is the author of No Apparent Distress: A Doctor’s Coming of Age on the Front Lines of American Medicine. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times Book Review and the New Yorker and does not represent the viewpoint of any hospital or health system with which she is associated.

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “A Cure for What Ails Us?” Subscribe today.