Larry McMurtry was missing the good ol’ days. In the introduction to his 1968 book of essays, In a Narrow Grave, he lamented our state’s fraying image in the global imagination. The Kennedy assassination and Johnson administration had tarnished our reputation. “We aren’t thought of as quaintly vulgar anymore,” McMurtry wrote. “Some may find us dangerously vulgar,” he added, before twisting the knife, “but the majority just find us boring.”

McMurtry needn’t have worried. If Texas was regarded as a tedious topic in the late sixties, it wouldn’t stay so for long. The next decade’s energy crisis was very good for domestic oil’s bottom line, and as we got richer, we got shinier. By the end of the seventies, Texans had so captured the country’s imagination that New York fashionistas were promoting a trend that sounds comically oxymoronic to the rest of us: Texas chic. Our socialites were mainstays at Studio 54, and not one but two Manhattan cowboy boot shops sold Texas footwear to the likes of Catherine Deneuve, Halston, and Liza Minnelli. A Broadway musical based on Larry L. King’s The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas won two Tony awards in 1979, and there was a popular Greenwich Village nightclub called the Lone Star Cafe. Waylon and Willie and the boys topped the country charts, and a nation lusted after a poster of a Corpus Christi native named Farrah with feathered blond hair and a ruby-red swimsuit. The Dallas Cowboys were America’s team, and the Cowboys cheerleaders were America’s sweethearts. The seventies, in short, were great for Texas. But no year added more girth to our britches than 1980, the year John Travolta rode a mechanical bull and somebody shot J.R.

Dallas, an hour-long melodrama series, premiered on CBS in spring 1978. The network had been looking for a glitzy saga, something with money and scandal, and the show’s creators, David Jacobs and David Paulsen, neither of whom were from Texas, felt such a thing simply had to be set amid the state’s famously sprawling ranches. Of course, knowing little about where Texas’s famously sprawling ranches actually were, they set the series in Dallas.

The show was not immediately well received, especially by Dallasites, who resented the stereotypes: the avaricious oil family, the ubiquitous cowboy hats. And no character better embodied the show’s ham-fisted caricature of Texans than J. R. Ewing, the show’s antihero, who was played by an actual North Texan, Weatherford’s Larry Hagman. But soon it wouldn’t matter how Texans felt about the show.

On March 21, 1980, Dallas’s third season ended with a cliff-hanger that will forever be mentioned anytime anyone anywhere talks about the history of television: J. R. Ewing, working late in his seemingly empty office, hears footsteps and calls out, “Who’s there?” before getting shot twice in the gut and crumpling to the floor.

“That episode was a groundbreaking piece of work and a true cultural phenomenon,” says Tom Schatz, a professor emeritus at the University of Texas at Austin’s Radio, Television, and Film program, who taught his students about Dallas for decades. A Midwesterner by birth, Schatz had moved to Texas in 1976 and quickly saw his new home gaining more cultural relevance, thanks to the popularity of outlaw country and the Austin City Limits television program. “Dallas took it all to another level, though,” he recalls.

It would be eight months before the question “Who Shot J.R.?” found an answer, but that didn’t stop people from asking. Literally, People magazine used that exact headline on its cover that summer along with a photo of Hagman in a wheelchair, with a plaid blanket across his legs, and his arms raised in an “I dunno” shrug. It was, it seemed, all anyone talked about. Even Queen Elizabeth’s mother brought it up when she met Hagman at her eightieth birthday celebration in England later that fall.

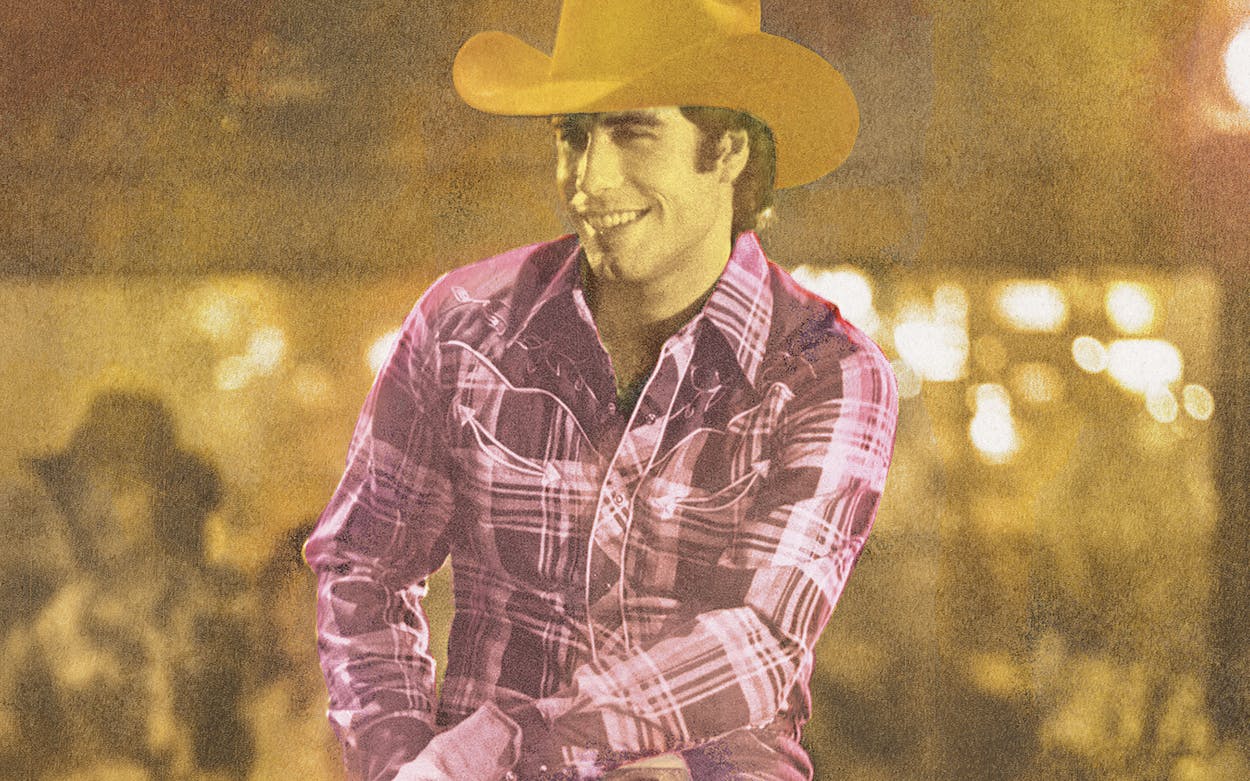

This is the scene into which Urban Cowboy two-stepped, on June 5, 1980, at a suburban movie theater in Houston, with an after-party at Gilley’s, the legendary honky-tonk where the film is set. Urban Cowboy was itself a by-product of the Texas chic trend, having been based on an Esquire article that was part of a wave of Texas coverage by national magazines (including entire special issues of Atlantic Monthly and Town & Country). The after-party was a whole to-do, hosted by international socialite Lynn Wyatt, with a guest list of about 3,500, including the film’s stars, Travolta and Debra Winger, as well as such glitterati as Andy Warhol and fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg.

Urban Cowboy’s instant success was jarring for some Texans. “Lord help us now. We’re in,” wrote Corpus Christi Caller-Times columnist Jerry Norman, just a week after the film premiered. “It’s been coming on for a long while, but now it’s here. Texas is the place; Texas chic is the thing.” Norman wasn’t wrong. America was a country obsessed. Bars that had been dedicated to disco or rock started playing country and western music and installed mechanical bulls. David Letterman rode one on a nationally televised morning show. The film’s soundtrack, which was chock full of “light country” fare that sounded more like Hall & Oates than Willie & Waylon, climbed to number three on the Billboard 200 chart. (One single, Johnny Lee’s “Lookin’ for Love,” was so ubiquitous, Eddie Murphy famously performed it as Buckwheat on Saturday Night Live the next year.) Dressing like a Texan became à la mode. The Sakowitz family (Lynn Wyatt was a Sakowitz), who ran an upscale Houston department store, expanded to Dallas, Midland, and Tulsa during peak Texas chic.

“Urban Cowboy was tapping into a phenomenon that preexisted the movie,” says Schatz of the film’s popularity. “But like Dallas, it generated much more heat than it was tapping into.”

That heat wave went global. Dallas was exported to ninety countries and translated into 67 languages. On November 21, 1980, when the show finally revealed who shot J.R. (spoiler alert: it was his sister-in-law/mistress Kristin Shepard, played by Mary Crosby), a reported 350 million people tuned in, including 83 million Americans (a then record) and, we presume, at least one member of the British royal family. The show was so popular in France that, despite the French government’s grumblings about excessive American cultural influence, its state-owned Channel 2 created a knockoff series. Dallas was the only American television show broadcast in then-communist Romania, and some say its popularity helped fuel the Romanian revolution in 1989. In fact, Dallas had all of Europe in such a cultural choke hold that the European Community (the precursor to the European Union) tried—and failed—to establish a rule limiting the amount of American TV that could be shown in member countries.

But back at home, the good times didn’t last. Oil peaked at $31.77 a barrel in 1981 and started a descent that would end with the 1986 bust. By 1982, Jackson, Mississippi’s Clarion-Ledger had declared “Texas Chic no longer in vogue.” Even Dallas’s ratings record was short-lived; in 1983, 105 million Americans watched the season finale of M*A*S*H. By 1990 Dallas had dropped out of the top thirty in the Nielsen ratings, and Sakowitz shuttered its last store.

But no one would ever again regard Texas as boring. (Larry McMurtry found new things to criticize about his home state.) In 2023 New Yorkers are once again wearing cowboy boots, pearl-snap shirts, and Stetson hats, only today they’re calling it Westerncore and attributing it to the popularity of Yellowstone, the creation of another Weatherford talent, Taylor Sheridan. You can still find Texas flags used as wall flair in random Parisian cafes; our barbecue has been exported to England, France, and Australia; and figures such as Selena, Megan Thee Stallion, and Richard Linklater have shown the world sides of our state that the Ewing clan could have never imagined.

Not all of this attention has been good, however. In Norway, for example, the word “Texas” is slang for “crazy.” But crazy is better than boring.

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of Texas Monthly with the title “The Year Texas Went Worldwide.” Subscribe today.

- More About:

- Film & TV

- Television

- Film